EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- A pre-election survey among Malay voters in Selangor found that there is no significant vote transferability between Pakatan Harapan (PH) and Barisan Nasional (BN). This means that BN Malay voters may not necessarily transfer their votes to PH candidates in the state election, and vice versa, despite the two parties forming a coalition government at the federal level.

- With a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of RM343.5 billion, Selangor is the highest contributor to Malaysia’s GDP and the epicentre of its economic development. As such, the election in the resource-rich state of Selangor will be very competitive and keenly contested by all parties.

- The survey also found that there is greater likelihood that BN Malay voters will transfer their votes to Perikatan Nasional (PN) candidates instead, thus giving it the advantage in the election, especially in 39 Malay-majority seats in the state. A party must win at least 29 out of 56 seats in the state assembly to get a simple majority to form the next state government of Selangor.

- With this latest polling trend, winds of change are blowing in Selangor. Whether or not these winds can sweep PN to an electoral victory in the state depends on how much strength they gather leading up to polling day.

- The survey used a face-to-face interview method, and was conducted by Institut Masa Depan Malaysia from 1 March to 20 April 2023. It collected 1,200 samples across ethnic groups in 39 Malay-majority state seats in Selangor in order to explore the dynamics of voting behaviour with a special focus on vote transferability among Malay voters. This paper examines its sub-sample of 850 Malay voters.

Editor's Note: This article was first published in ISEAS Perspective 2023/50, 5 July 2023

ARTIKEL BERKAITAN: Selangor dalam genggaman PN: 39 kerusi majoriti Melayu dijangka menolak calon PH-BN, menurut kaji selidik terbaharu

INTRODUCTION

One plus one in politics may not necessarily be equal to two. It could instead be one-and-a-half, or one, or even zero. This unwritten rule in politics applies to political coalitions too. It may not be accurate to assume that the formation of a coalition, especially among rivalled and ideologically incompatible political parties, will benefit those parties in an election. Instead, each party runs the risk of losing their core supporters should there be no vote transferability between them.

By vote transferability we mean that supporters of party A, which forms a coalition with party B, will transfer their votes to party B in an election, and vice versa. If there is full vote transferability, both parties will enjoy net gain in an election. But if there is no vote transferability, there is not much that the parties gain from the collaboration. Or worse, both parties may lose out should their supporters disagree with the coalition and transfer their votes to party C instead.

Political developments in Malaysia after the 15th general election witnessed the formation of a political coalition comprising rivalled and ideologically incompatible political parties to form a federal Unity Government led by former jailed Opposition Leader and Pakatan Harapan (PH) Chairman Anwar Ibrahim. The post-election arrangement between the leaders of two rival coalitions, PH and Barisan Nasional (BN), has paved the way for the appointment of Anwar as the Prime Minister and BN Chairman, Zahid Hamidi, as the Deputy Prime Minister.

While party elites try to accommodate each other for the sake of forming the government and maintaining stability, the same cannot be said for party grassroots. Within UMNO, the leading component of BN, grouses have been simmering among the conservative Malay party grassroots who questioned the party’s ‘unholy alliance’ with its archrival secular Democratic Action Party (DAP), a leading component of PH, which UMNO has long been accusing of being an anti-Malay party.

As PH and BN will participate in the upcoming state elections as coalition partners, the issue of vote transferability between the two parties has become a vital consideration. Will BN Malay voters transfer their votes to PH candidates, in the event of a straight fight between PH and PN in their constituencies? Or will there be a vote swing to PN candidates instead?

Seeking answers to these questions, we conducted a survey of eligible voters in the crown jewel state of Selangor, with special focus on Malay voters. Selangor is foreseen to be the main battleground in Malaysia’s 2023 state elections. With GDP of RM343.5 billion in 2021, Selangor is the largest state economy in Malaysia, and has been under PH’s rule (formerly Pakatan Rakyat) since 2008.

THE SURVEY’S METHODOLOGY

This survey began on 1 March 2023 and ended on 20 April 2023, and all in all, 1,200 samples were collected.[3] Voters’ demographic profile, spanning across age, ethnicity and gender, is based on the most recent fourth quarter Election Commission electoral roll data. Malays made up 54% of Selangor’s population, Chinese 32%, Indian 13%, and other races 1%. As the focus of this study is to explore the dynamics of Malay voters’ party choices, the ethnic composition for this study was re-adjusted to 69% Malays, 18% Chinese, 12% Indian, and 1% other ethnicities, which approximately reflects voter demography in 39 Malay-majority state constituencies.

The samples collected throughout the selected constituencies stood at 24% rural, 35% urban and 41% semi-urban areas. We also managed to reach out to respondents in the age groups that relatively reflect current voter configurations, i.e., 18-20 years old 8%, 21-35 years old 46%, 36-50 years old 15%, and above 51 years old 31%. We applied the face-to-face interview technique as our data collection method.

KEY FINDINGS OF THE SURVEY

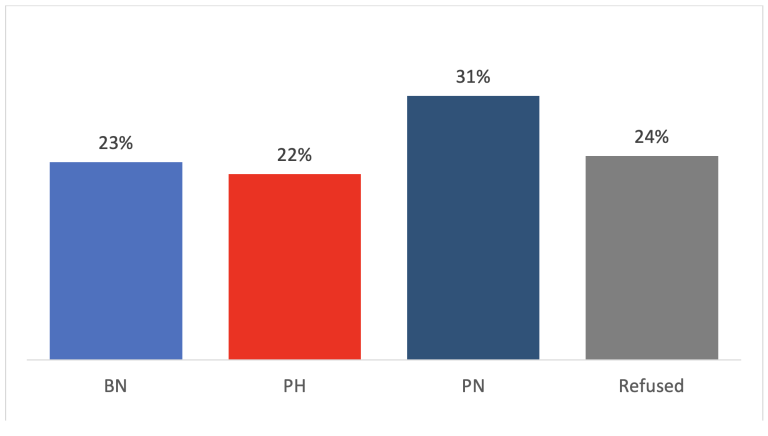

To find out the extent of vote transferability among Malay voters, we asked our Malay respondents the party that they voted for in GE15 and the party that they will vote for in the 2023 state election. We found that 23% of them said they voted for BN, 22% for PH, 31% for PN and 24% refused to answer (See Figure 1).

This finding reflects Bridget Welsh’s GE15 estimate of Malay support for political parties in Selangor, i.e. 23% for BN, 24% for PH and 49% for PN.[4] The only difference is that the Malay support for PN shown in our study is lower than Bridget’s estimate. Taking her estimate as a reference point, we believe that many of our respondents who refused to reveal their party of choice in GE15 could be PN voters.

Figure 1: Parties the Malay respondents voted for in GE15.

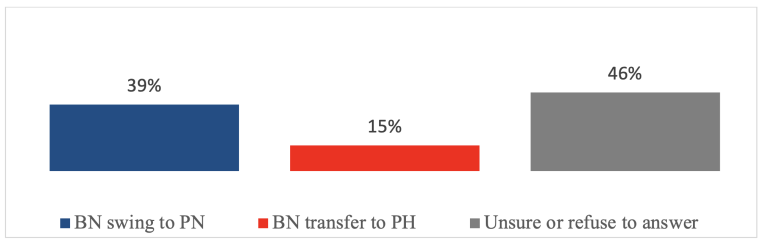

The survey saw 39% of Malay voters in Selangor who voted for BN in GE15 saying that they will vote for PN in the upcoming state election if there is a straight fight between PN and PH in their constituency. Only 15% said they will vote for PH (See Figure 2).

This means that there is no significant vote transferability between PH and BN Malay voters in Selangor despite the fact that the two coalitions are partners in the Unity Government at the federal level. On the contrary, a significant percentage of BN and PH Malay voters are more inclined to vote for PN candidates, while many of them turned into “unsure voters”.

Figure 2: Among Malays who voted for BN in the November 2022 general election, how will they vote in a PN vs PH contest in the 2023 Selangor state election?

This means about seven out of ten BN Malay voters who have made up their minds on party choices clearly indicated that they will vote for PN, instead of PH. The survey also found that a whopping 46% of BN Malay voters have fallen into the “unsure voters” category, which indicates BN’s shaky support base at present.

Determining the voting preferences of these “unsure” BN Malay voters is a tricky business. However, historical data and past trends may shed some light on its likelihood. It is an unwritten rule of thumb for Malaysian pollsters to allocate to the opposition parties a greater percentage of those in the “unsure voters” category for a few reasons.

First, these voters might have made up their mind on their party of choice but refused to disclose it for fear of retribution, especially if they are supporting an opposition political party. Second, as these voters voted for BN in the last general election, being “unsure” this time round indicates a shift of support away from the party or its allies.

Therefore, based on historical data and past trends, we estimate that at least 60% of these “unsure” voters are more likely to vote for PN, instead of PH. Furthermore, cross-tabulation of data on party choice, perception of party leaders, government approval rating and agreement or disagreement with the formation of the PH-BN coalition government shows that the majority of the unsure BN Malay voters are pro-PN.

With 39% of the BN Malay voters clearly indicating that they would vote for PN and approximately 60% of those in the “unsure voters” category potentially doing the same, we therefore roughly estimate that at least 67% of BN Malay voters in Selangor will vote for PN in the upcoming state election.

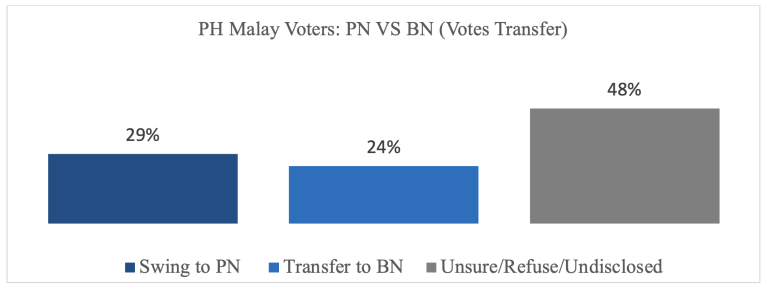

A similar trend could also be observed among PH Malay voters. The study found that, in the event of a straight fight between PN and BN, 29% of Malay voters in Selangor who voted for PH in the last general election intend vote for PN, while 24% will vote for BN and as much as 48% have to be classed under “unsure voters” (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Among Malays who voted for PH in the November 2022 general election, how will they vote in a PN vs BN contest in the 2023 Selangor state election?

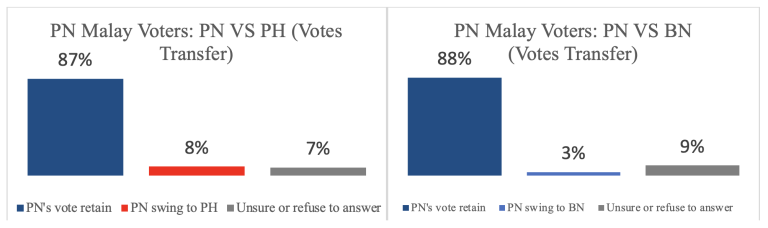

While for PN, its support base among Malay voters remains almost solid. In a straight fight between PN and PH, 87% of Malay voters in Selangor who voted for PN in the last general election said they would vote for PN. Only 8% would vote for PH and 5% were unsure. Similarly, in a straight fight between PN and BN, 88% of them said they would vote for PN. Only 3% said they would vote for BN and 9% were unsure (See Figure 4).

Figure 4: Among Malays who voted for PN in the November 2022 general election, how will they vote in a PN vs PH and PN vs BN contest in the 2023 Selangor state election?

Should this trend continue until polling day, PN will gain more from the ‘swing votes’ it will get from BN and PH voters than the small number of votes it will lose out to those two parties. Furthermore, since quite a significant percentage of BN and PH Malay voters have become ‘unsure’ of their voting preferences, they too are potentially vulnerable to PN’s narratives in the upcoming election.

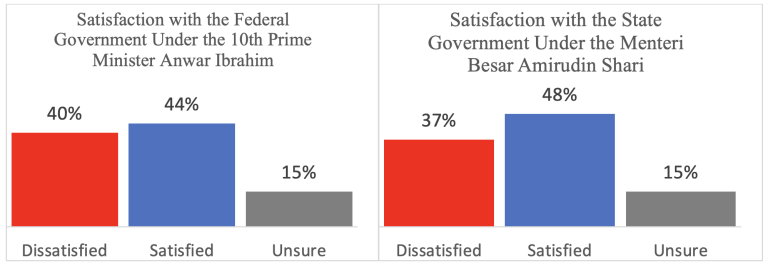

As a measure of party choices, we also looked at how the Malay voters considered the performance of the federal and state government as well as their perception of key political leaders. The survey found that only 44% of Malay voters in Selangor were satisfied with the performance of the federal Unity Government, and 48% were satisfied with the performance of the state government (See Figure 5).

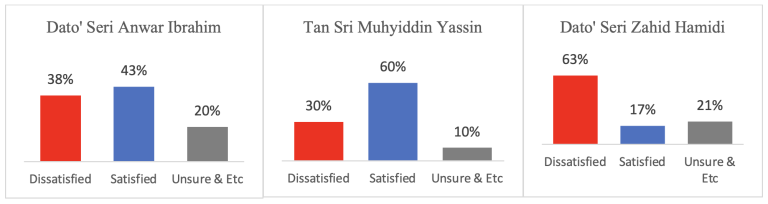

On the Prime Minister’s approval rating, 43% said they were satisfied with the performance of Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, compared to 60% who said they were satisfied with the performance of former 8th Prime Minister, Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, who is also PN Chairman. BN Chairman and Deputy Prime Minister, Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, received the lowest approval rating; only 17% said they were satisfied with him (See Figure 6).

Figure 5: Satisfaction Towards the Federal and State Government

Figure 6: Perception of National Leaders’ Performance

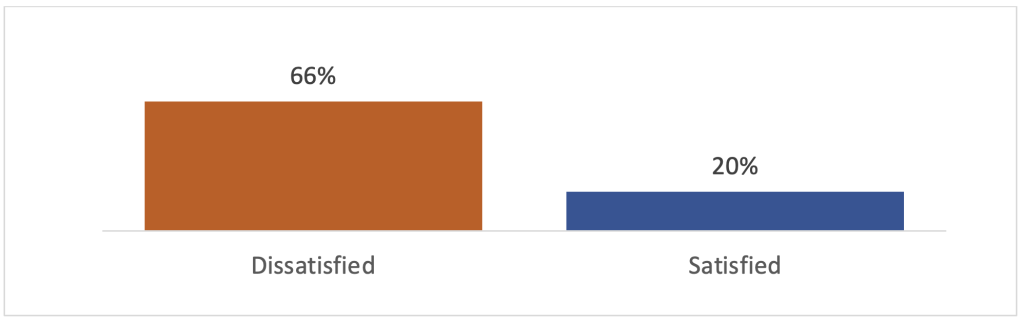

On the economy, only 42% were satisfied with the way the federal government has managed the country’s economy, with 57% of them saying their personal income was worse than the previous year. Inflation and the cost of living topped the list of problems faced by the voters at 60%, followed by corruption 7%, infrastructure development 6%, economic development and job opportunities 4% each and political instability, racial rights, and welfare 3% each. On these specific issues, only 20% of Malay voters were satisfied with the way the government handled them (See Figure 7).

Figure 7: Perception of Government’s Effort to Solve Issues Raised by the Respondents

While low vote transferability may make it difficult for the PH-BN coalition to retain power in Selangor, the problem is further complicated by the lack of “performance legitimacy” that is much needed by the PH-BN coalition as an incumbent government. As the federal Unity Government has been facing intense criticisms for its lackluster performance in managing the country’s economy and addressing inflation and cost of living, incumbency can be a liability for PH and its ally, the BN.

WHY IS THERE NO FULL PH-BN VOTE TRANSFERABILITY?

The post-election arrangement between PH and BN to form a coalition government at the federal level, followed by similar arrangements at the state levels, was clouded with possible voter rejection from the very beginning. While PH and BN political elites who stand to gain from the coalition seemed to be comfortable with the arrangement, grouses among party supporters had already been detected long before the two former political archrivals sealed their post-election cooperation.

A national survey conducted by the Merdeka Center for Opinion Research prior to GE15 revealed that only 32% of Malay voters agreed to the formation of a coalition between BN and Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), while 60% disagreed with the arrangement and 8% are unsure.[6] The findings were an early sign of non-transferability of votes between PH and BN Malay voters.

Malay voters’ rejection of such a coalition seems to be consistent with the findings of our pre-state election survey in Selangor, which shows that most of the BN Malay voters are persistent in their political choice by indicating that they will not transfer their votes to PH. Perhaps as protest against the formation of the coalition, they may transfer their votes to PN instead.

The outcome of the Padang Serai and Tioman by-elections held immediately after the GE15 was also an indication of low vote transferability between PH and BN. The by-elections were the first attempt by PH and BN to contest in an election as a coalition. The PH candidate lost by 16,260 votes to the PN candidate in the Padang Serai parliamentary constituency, which was previously a PH stronghold. The BN candidate won the Tioman state seat by a slim majority of 573 votes.

We believe that negotiations for post-election cooperation had been ongoing between the leaders of the two parties prior to GE15. The decision not to conclude or announce the cooperation prior to the election was a tactical move to avoid the problem of non-transferability of votes between the two parties.

Should the cooperation be announced before the general election, both parties risked losing the support of their core voters and faced a possible electoral defeat. However, the problem that the leaders of the two parties avoided in the GE15 has now come to the fore and must be dealt with in the upcoming state elections. Given the negative Malay voters’ sentiment toward the PH-BN coalition, especially among BN Malay voters, convincing them to vote for PH is an uphill task.

The BN Malay voters’ negative attitude toward the PH-BN coalition is rooted in the dynamics of ethnic politics in Malaysia. As one of the authors of this article has argued in an earlier ISEAS Perspective, ethnicity remains the key factor in determining voting preferences in Malaysia.

Since independence, UMNO has been the linchpin party of the Alliance and later the BN for six decades. UMNO’s narrative of Malay political supremacy against the threat of Chinese dominance in the economy, and subsequently in politics, has been very appealing to the majority of Malays. The Chinese-based Democratic Action Party (DAP), whose ideology is mainly shaped by the Setapak Declaration 1967, which promotes equality of all citizens and rejects the categorization of Malaysians into Bumiputera and non-Bumiputera groups, has been UMNO’s long-time archrival and bogeyman.

With strong Malay support for UMNO, BN won every general election and emerged as a dominant party in the past. However, Malay support for UMNO has gradually deteriorated since the 12th general election when it lost its customary two-thirds majority in the Dewan Rakyat followed by its loss of popular votes in the 13th general election, its electoral defeat to PH in the 14th general election and its dismal performance in the 15th general election in winning only 26 seats, the lowest number of parliamentary seats the party has ever won.

The deteriorating Malay support was mainly due to the party’s diminishing “performance legitimacy”. Having been the ruling party for more than five decades, the party was mired in allegations of corruption involving its leaders and failures to address pressing economic problems faced by the people. The 1MDB saga which led to the trial and conviction of former Prime Minister and UMNO President, Datuk Seri Mohd Najib Tun Abdul Razak, on corruption charges, as well as the ongoing corruption trial of the Deputy Prime Minister and UMNO President, Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, diminished the Malays’ trust in UMNO leadership. To make it worse, internal UMNO politics have since revolved around defending its tainted leaders, which has in turn intensified the negative public perception toward UMNO, created splits among party elites, and weakened the party.

At the same time, the social and economic changes taking place in Malaysia since the 1990s, which marked the end of the New Economic Policy (NEP), eroded UMNO’s role as the sole Malay protector. More and more Malays from villages migrated to urban centers in search of a job, education, and business opportunities, hence uprooting and alienating them from the traditional UMNO’s patronage system.

From the 1990s onwards, the more liberal economic, education and cultural policies adopted by the government as a response to domestic political pressures and the need to compete globally in the age of global capitalism, has gradually reduced Malay dependency on UMNO. The new Malay middle class no longer enjoys the long list of “privileges” and “crutches” provided to the generations before them. They must now pay for their children’s higher education and compete with the non-Malays for government scholarships, entry into public universities is gradually being based on merits rather than race-based quota, and more and more Malays have to face intense competition in the private sector instead of the public sector for better jobs and better pay.

UMNO’s diminishing role in securing economic benefits to the Malays through a wide range of affirmative action policies and addressing their economic plights post-NEP, especially for those in the lower income bracket, has caused the party to gradually lose its performance legitimacy in the eyes of the Malay community. The diehard UMNO supporters who continue to support the party do so solely based on its “race legitimacy”, i.e. psychological and nostalgic reasons relating to a deep appreciation of UMNO’s past struggle for the Malays and the belief that UMNO was the last Malay bastion.

For most UMNO Malays, the feat of non-Malay economic and political superiority is strong and UMNO has been their only hope against such a threat. Therefore, the “NO ANWAR, NO DAP” slogan sat deep in the conservative UMNO Malay psyche in GE15. Anwar represents the non-conservative Malay leader who rejects Malay supremacy as a political ideology, while DAP is UMNO’s long-time political foe whose ideology of racial equality runs counter to UMNO’s core struggle as a Malay party.[10] A recent statement made by former UMNO Secretary-General, Ahmad Maslan, “ordering” the party’s supporters to vote for DAP was internally conflicting and was rejected by several party leaders.

At the very least, the “NO ANWAR, NO DAP” slogan kept the UMNO Malays loyal to the party up to GE15. However, with the party leadership’s decision to form a post-election coalition government with PH, in which its archrival DAP is a dominant coalition member, the conservative UMNO Malays’ trust in the party was crushed. For them, that was like the final nail in UMNO’s coffin. The party’s “race legitimacy”, to which the remaining diehard conservative UMNO Malays still clung, is completely gone.

But these conservative UMNO Malays do not stop there. In the upcoming state elections, they can still make their own choice as voters. Hence, as our survey found, seven out of ten BN Malay voters in Selangor who have made up their minds on party choices, have decided to vote for PN. It seems that PN, led by the pribumi-based BERSATU and the Islamist party PAS, is the natural alternative to BN for the conservative UMNO Malays. PN represents the imagery of Malay and Islamic conservatism that UMNO abandoned by virtue of its cooperation with DAP.

Apart from this, PN’s narrative of good governance, anti-corruption, and care for the people, as shown by the various fiscal and non-fiscal assistance given to the people through the eight economic stimulus packages rolled out during its 17 months in power, captured the imagination of Malay voters and convinced them that PN may be a better alternative to UMNO.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SELANGOR STATE ELECTION

This paper does not attempt to predict election results based on a pre-election survey held two months before the state assembly is dissolved. Instead, we believe that the upcoming state election in Selangor will be very competitive, and the actual results will depend on the campaign narratives of all the parties as well as the candidates and on other local factors.

What this survey can tell us is the general trend that can be observed at the time the survey was conducted. And the general trend is, the support base for PN among Malay voters remains solid, and the party may receive potential swing votes mostly from BN Malay voters and some from PH Malay voters. There is no significant vote transferability between PH and BN among the Malay voters in the crown jewel state of Selangor.

There are 56 seats in the Selangor state assembly, of which 39 are Malay-majority seats and 17 are non-Malay majority seats. The simple majority needed to form the state government is 29 seats.

A simple and straightforward simulation of the GE15 results expects the PH-BN coalition to win the state election by more than a two-thirds majority. However, this may only be true if there is full vote transferability between PH and BN voters. Our survey shows this not to be the case.

This survey suggests that there is a greater de-alignment between voters and UMNO which is primarily contributable to the BN Malay voters’ rejection of the PH-BN cooperation, clash of party ideologies and the existence of rival parties that shared identical ethno-religious roots. Furthermore, with the PH-led Unity Government lacking in visible efforts and policies to address the rising cost of living and to ease inflationary pressures, there is no feel-good factor that incentivizes voters to support the coalition in the election.

With this trend in mind and based on the GE15 election data for all the state constituencies in Selangor, we believe that PN is comfortable in at least 15 Malay-majority seats. We also assume that PH is safe in all the 17 non-Malay majority seats.

Which party will form the next state government in Selangor depends on the outcome of the contest in the remaining 24 Malay-majority seats. Should the swing of BN Malay voters towards PN be strong enough to tilt the balance in PN’s favour, PN will have an advantage over PH or BN in the contest for these seats. Thus, these seats will be keenly contested by all political parties.

CONCLUSION

Forming a workable and stable coalition requires not only elite accommodation, but also a certain degree of acceptance at the grassroots level. As this study shows, against the wishes of the BN party elites, its grassroots’ acceptance of the PH-BN coalition is still highly questionable at this moment. If left unchecked, it will destabilize the coalition in the long run.

With this latest polling trend, the winds of change are blowing in Selangor. Whether or not these winds can sweep PN to an electoral victory in the state depends on how much strength they gather leading up to polling day. - DagangNews.com

ENDNOTES

For endnotes, please refer to the original pdf document. ISEAS Perspective is published electronically by: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

* Marzuki Mohamad is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science, Abdul Hamid Abu Sulayman Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia. He is also a trustee of Institut Masa Depan Malaysia (Institut MASA), a local think-tank focusing on social, economic, and political research. Khairul Syakirin Zulkifli is Researcher at Institut MASA. This article is written in both authors’ personal capacity.